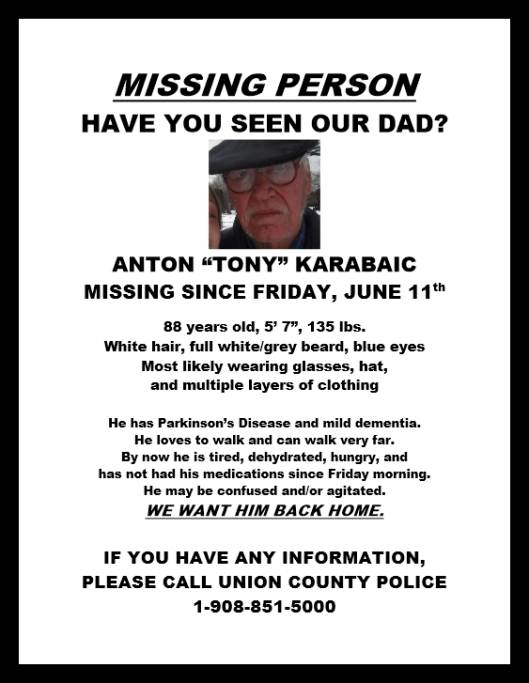

Tuesday, June 15th, 2010

That day is a blur; it was supposed to be my day of rest, after going out to Union to search for Dad on Saturday, Sunday, Monday. I had set Wednesday as my return to work, if we didn’t find him. I had very mixed feelings about going back to work. I couldn’t stay out indefinitely; what if we never find him? Sometimes, people who go missing are never, ever found. They just disappear without a trace. How does a person just disappear? The laws of physics tell us that matter cannot be created or destroyed in a closed system; therefore, he can’t just be gone. He is somewhere in the Escheresque universe in which I’ve been living since 8:40 Friday morning; I just can’t find my way to him. The angles are all wrong, they are impossible, incomprehensible.

I’ve been saying: “My dad is missing”. I could just as easily say: “I’m missing my Dad” and mean it in all its double-entendred glory; he’s missing; I miss him; oops, have I missed him? What am I missing?

When someone goes missing, what happens to the people who are missing them? What do they do? Do they return to their jobs? Do they shop for groceries on the way home from work? Do they still buy Metrocards, and make sure that there’s milk in the refrigerator for breakfast the next morning? Do they plan their meals for the coming week? What about the laundry? Do they carry on, do they do all of these things, all the while waiting for a call from the police or the FBI or a hospital or a morgue that their loved one or their loved one’s body has been found?

Or do they simply sit still? Do they wait by the telephone, or stake out a spot in front of the computer, searching, researching, unable to move? Do they take their cellphones into the shower? Do they take showers? Whatever I am doing, I feel like I should be doing something else instead. What if I’m doing the wrong things, and that’s why I can’t find the right angle? Is my approach all wrong?

I don’t know how to do this. If we don’t find him, I don’t know what we will do.

I’ve never known anyone else who had this happen. I have no experts to consult. I need a roadmap for this terra incognita where we are marooned.

My plan for Tuesday was to talk to the detectives in the morning and get them to set the bloodhounds looking for my father. We were in Day 5; Dad had been missing for ninety-six hours (I had decided that, when we got to one hundred hours, I would switch to counting days). Frank and I awoke to the alarm, took our showers, ate our breakfast, drank our coffee, shared the New York Times, watched Weather Channel, just like we do every day. It was all so nice and normal.

I turned on my computer to check email. I had messages from my friend Janice asking if there’d been any word (no); from my friend Peg, who pointed out how easily the elderly become invisible to the rest of us, allowing as how if Dad had gone out in his pajamas, someone might remember having seen him (he had done that already, the week before); from Nancy, letting us know that she, Chris and Grant would be in New Jersey by around 2 that afternoon. She added that Chris suggested that one way to get Dad back would be to buy and install an air conditioner in his dining room (Dad was legendarily spartan about heating and cooling).

The detectives called me while I was still at my computer, sometime after 9AM.

Det. Moutis confirmed to me that today was the day that the bloodhounds would search the woods while the helicopters flew over.

Today was the day that Dad would be found, but I didn’t know that yet.

The search had become its own creature, apart from Dad; Dad and the search for Dad were two separate beings. There had been moments when I felt we were searching just for the sake of doing something. It wasn’t that I thought our efforts were useless or hopeless; there was a small (and shrinking) part of me that thought we might yet find him, and find him alive. Surely there was a reasonable explanation for him being missing; the Laws of the Conservation of Matter decreed that he was still somewhere in the known universe.

What I would say, or do, if I saw my father sitting on a park bench, or walking down a side street?

Would I run up to him, hug him and kiss him and ask him if he was hungry, thirsty, tired?

Come to Me, all who are weary and heavy-laden, and I will give you rest.

Would I just stand there, mouth agape, unable to speak?

Would I even believe my own eyes?

Would I yell at him for putting us through this living hell for almost five days?

Or would the stress of all of it, combined with the shock of seeing him again, cause my body to crumble into a pile of dust and blow away on the wind?

I do not know how to do this.

Since Friday, I had been dealing with the unknowingness of my situation by trying to control those things I could. To be effective, to move forward, I had to be dispassionate about the alternatives that lay before us. I had to be on task, I had to manage time well, I had to ruthlessly prioritize. It was like managing the store (people/product/operations), except this really was life and death. I wasn’t alone; I had lots of help, all the help I could ask for; my husband, my siblings and sibs-in-law, their children, our friends were living through this with me; but I felt so terribly alone.

These were the things I could control at this moment: I could check email and respond; I could talk to people on the phone; I was home this day, so I could do research online to find something, anything; there had to be something, and I was just missing it.

I had promised Frank I would try to rest, just this one day; I planned to take a nap at some point, lie on the couch with the windows open (the weather had been so gorgeous since Friday) and let myself drift…

But first… I had to…

Okay, so the detectives would have dogs and helicopters … Det. Moutis said that we should register for a Silver Alert. I said I’d set it up if he sent me a link.

As soon as we got off the phone, I followed up with him by email, confirming the details of their plan for the day, and copying my sibs; I asked if the police had issued a general press release yet, because some news outlets would do nothing without something from the police.

Monday night, when I got home from New Jersey, before we had dinner, Frank and I were talking about places that George and Barbara and Alyssa and Kevin and Glenn and the neighbors and I couldn’t get into to search on our own. Frank had made a list of the kinds of places that should be searched; abandoned buildings within a reasonable radius; houses that had been foreclosed upon, and were vacant; garages, sheds, outbuildings, even on occupied properties—we’d had a cat years ago who had gotten locked in a neighbor’s garage by accident, and he’d been missing for three days before the neighbor returned, opened the garage, and out came our Patch. Maybe Dad crawled into or under an abandoned car in a foreclosed garage and has been unable to get out and come home. Maybe he fell through a rotted floor in a vacant, derelict house. Maybe he got lost again, and went into a house that he thought was his, except it was empty, and now he thought we had sold all of his things or that he had lost the house to taxes. When we had his income taxes done earlier that spring, he got confused, and thought the new accountant was there to take his house away. Maybe he was looking for Mom.

I asked Det. Moutis if anyone had searched abandoned buildings in the area, homes that were vacant due to foreclosures, sheds, outbuildings, anywhere where someone who was tired, lost, and scared might crawl in to get some rest.

Come to Me, all who are weary and heavy-laden, and I will give you rest.

I asked Det. Moutis if we should hire a private detective. Would that help or hinder the police effort?

I told Det. Moutis that Nancy and her family were coming in that afternoon, that John would be arriving Thursday, and that my siblings and I had decided that I would be the point of contact in order to streamline our communications.

My email to Det. Moutis crossed with his email to me giving me the web address for setting up a Silver Alert. I should have guessed it—www.silveralert.org – and I can’t remember now why I couldn’t. I registered my dad for the Silver Alert and uploaded the picture that we’d used on his flyers. I emailed the link to Det. Moutis and all my sibs with the login and password. For some reason—and I don’t know if it still works this way—the login and password were only good for an hour, and I had to re-log-in and re-upload his picture once the hour was up.

How do people who really are alone in their search for their missing loved one manage the logistics? You have to be at least three people at the same time to do everything that needs to be done; one to be out in the world, searching, one to be researching new places to search, and one to be the operations point person coordinating the searches and eliminating time-wasting redundancies and duplications of effort.

It helped me to try to think of all of this as a management problem, which could be broken down into small, discrete components, and thus be solved.

I called my contact at Union’s Channel 12 to give her Dad’s information and the Facebook page URLs so she could do a screengrab of the flyer. I promised to follow up with a flyer by email, in case the screengrab wasn’t sufficiently clear. Lexi promised to get the information on the air that day.

Janet and Wally were at Dad’s, getting ready to leave for Maryland, since Nancy was coming up. Someone had to be in Maryland to take care of the total of five cats and one dog between the two households, so Janet and Nancy tag-teamed. I think that George and Barbara were both back at work—it’s so hard to remember now, and my cell phone and text records aren’t clear. Alyssa had finals coming up, so she was back in school. John was planning to arrive on Thursday. Maybe we’d find Dad by then.

At the same time we were searching for Dad, we each had to consider the possibility of needing to take time off from our jobs to plan and hold a funeral.

We had arranged for Glenn to be at the house to meet the detectives and the canine unit, so that the dogs could start the search and (we hoped) find Dad. I texted Glenn to let me know when the police arrived.

Done with email, done with the phone, I turned up the ringer on the answering machine in the studio, left my computer, turned on the television to a channel that only played New Age relaxation music, and I lay down on the couch.

Come to Me, all who are weary and heavy-laden, and I will give you rest.

I drifted in and out, aware of the music and the traffic noise from Northern Boulevard, coming and going.

The phone rang: it was Glenn.

The detectives had arrived, with the bloodhound and his handler from the Essex County Canine Unit. It was mid-day. They’d had to wait for the bloodhound to come from the next county, because Union County didn’t have one of their own.

This is what Glenn told me:

The handler needed a scent article for the dog. They used the pajamas that Dad had left on the dining room chairs.

The handler, wearing latex gloves, took my father’s old worn pajamas outside, and spread the top and bottom out on the lawn in front of Dad’s house. (The image I conjured for myself of my father’s nightclothes spread out on the lush grass is indelibly imprinted on my mind’s eye.) The handler wears gloves so that he doesn’t transfer his own scent particles to the scent article.

The dog sniffs and paws at my father’s garments on the grass not too far from the huge oak tree; the dog gets Dad’s scent.

After a minute or two, the leashed bloodhound pulls back from the pajamas, excited, hyper, panting, wanting to go. His handler settles him, looks the dog square in the eyes.

“Do you wanna go find him, do you wanna go find him?”

The bloodhound—his nose to the ground—and his handler quickly turn and head down Huntington to the corner of Livingston; they turn left, and go down the incline (it is not quite a hill).

(Glenn didn’t see this next part. He will recount this to me in our next conversation, after he speaks with the detective by the park:

The dog and handler crossed Forest Drive, and approached the shortcut path that cuts through the woods to Salem Road.

The dog veered left at the head of the path, into the woods, without hesitation.)

Glenn stays at my father’s house. He is waiting.

I am in my living room. I am waiting, too. I text Glenn (not wanting to tie up the phone); he has heard nothing, and is getting anxious. They have not been gone long.

Sometime, not too much later, one of my father’s neighbors, a woman, tells Glenn that there is a police car and an ambulance at the little park across the street from Union Hospital.

Glenn thinks he knows what that is about, and he drives down to see. He meets the detective where the park’s grassy half-circle meets the woods.

They have found a body deep in the woods. Glenn wants to go, but the detective shakes his head, tells him he won’t be able to identify him.

The bloodhound veered left at the head of the path, into the woods, without hesitation. They went deep, deeper, following my father’s scent, over brambles, and weeds, and thickets of vines, into the heavy brush. They found him lying on the ground.

Glenn comes back to Dad’s and calls me and tells me what he saw and heard.

I thank him.

Come to Me, all who are weary and heavy-laden, and I will give you rest.

I don’t remember the details exactly. I think at some point, not too long after, Det. Moutis called me.

They found the body of an elderly man, a man they believed was my father, in the woods, about fifty yards from where the grassy half-circle of park begins.

He said it would have been impossible to find him without the bloodhound. The brush and tangles of vines and weeds were more than two feet high; Dad had sat down on a log, taken off his shoes, and either lay down or fell back. He was on the ground, his glasses and tan hat were off to the side, his watch still on his wrist. He was clothed except for his shoes, which were on the ground next to the log.

They would have to confirm his identity with dental records. He had been out in the elements for more than one hundred hours. The coroner would later say that he had almost certainly died the first day. That would account for the lack of sightings, I thought to myself.

Nancy, Chris, and Grant arrived at Dad’s house at about the time that the detectives were calling me. I must have called Janet and Walter, John and Cheryl, Barbara and George, but I don’t remember doing so. Frank came home sometime in the late afternoon and I told him. I am sure I was crying, but I don’t remember. I texted my friends. I called the store and told Emery that they had probably found my father, and I wouldn’t be coming in on Wednesday after all.

Come to Me, all who are weary and heavy-laden, and I will give you rest.

_________________________________________________________________

Do you like what you’re reading here at my blog?

Do you want to follow me?

Click on the Follow Blog Via Email link in the left margin and subscribe.

You can also connect with me on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, or LinkedIn.

THANKS!